Hepatită autoimună de tip 1 asimptomatică cu nivel normal al IgG şi deficit de IgA – prezentare de caz

Asymptomatic autoimmune hepatitis type 1 with normal IgG level and IgA deficiency – case report

Abstract

Introduction. Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) in children is a chronic inflammatory liver disease with a broad clinical spectrum, ranging from isolated elevated transaminases to acute liver failure. AIH is a rare condition, with an increased prevalence in the last years (2.4-9.9 per 100,000 children). Case report. We present the case of a young girl, 7 years old, who was admitted to our hospital for an increase of liver enzymes, discovered accidentally. She was asymptomatic, and no physical signs of chronic or acute liver disease were found at admission. The laboratory parameters revealed increased transaminases without cholestasis. The viral causes of hepatitis were excluded, along with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and Wilson’s disease. She had a normal level of serum IgG and a low IgA level with positive antinuclear antibodies (1:80) and anti-smooth muscle antibodies (1:320), suggestive for the diagnosis of AIH type 1 and anti-liver kidney microsomal type 1 antibodies. The treatment with prednisone was started, and the evolution was favorable, with the normalization of laboratory parameters. Conclusions. This case highlights the importance of the early recognition of this pathology and the careful evaluation of any increased serum transaminases, even in asymptomatic children.Keywords

autoimmune hepatitischildasymptomaticautoantibodydiagnosisRezumat

Introducere. Hepatita autoimună (HAI) la copii este o boală hepatică cronică inflamatorie, cu un spectru clinic larg, de la o creştere izolată a transaminazelor până la insuficienţă hepatică acută. HAI este o afecţiune rară, cu o prevalenţă crescută în ultimii ani (2,4-9,9 la 100.000 de copii). Prezentare de caz. Prezentăm cazul unei fete în vârstă de 7 ani, care a fost internată în spitalul nostru pentru o creştere a transaminazelor, descoperită accidental. La internare a fost asimptomatică şi nu a prezentat semne ale unei afecţiuni hepatice cronice sau acute. Parametrii de laborator au relevat creşterea transaminazelor, fără colestază. Cauzele virale ale hepatitei au fost excluse, împreună cu deficitul de alfa-1 antitripsină şi boala Wilson. Pacienta a prezentat un nivel normal al IgG seric şi un nivel scăzut de IgA. Anticorpii antinucleari (1:80) şi anticorpii anti-muşchi netezi (1:320) pozitivi au fost sugestivi pentru diagnosticul de HAI de tip 1, dar pacienta a prezentat şi anticorpi antimicrozomiali ficat rinichi de tip 1. S-a administrat tratamentul cu prednison, cu o evoluţie favorabilă şi cu normalizarea parametrilor de laborator. Concluzii. Acest caz evidenţiază importanţa recunoaşterii timpurii a acestei patologii şi a evaluării atente a oricărei creşteri a transaminazelor serice, chiar şi la copiii asimptomatici.Cuvinte Cheie

hepatită autoimunăcopilasimptomaticautoanticorpidiagnosticIntroduction

Pediatric autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a form of chronic hepatic disease of uncertain etiology, characterized by hepatic cytolysis, circulating autoantibodies and/or increased levels of IgG. AIH is responsible for approximately 2-5% of the chronic liver diseases in children, but these numbers increase every year due to enhanced awareness and to an actual increase of the incidence(1,2).

The spectrum of pediatric autoimmune liver disease includes three disorders that present autoimmune mechanisms: autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis, and de novo AIH post-liver transplantation. AIH is divided into two types, based on the autoantibody profile: type 1 (AIH-1), with positive anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) and/or anti-smooth muscle antibodies (SMA), and type 2 (AIH-2), with positive anti-liver kidney microsomal type 1 antibody (anti-LKM1) and/or anti-liver cytosol type 1 antibody (anti-LC-1)(1). Autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis (ASC) is an overlap syndrome between AIH-1 and sclerosing cholangitis, characterized by inflammation and stenosis of the bile ducts and associated with the presence of autoantibodies, ANA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) in more than 80% of patients, and SMA in more than 60% of patients. ASC and AIH may be associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). For the differential diagnosis of ASC and AIH-1, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) should be used, as the autoantibody profiles are very similar(1,3).

The clinical presentation of AIH is very heterogeneous, including acute onset resembling viral hepatitis with nonspecific symptoms, acute liver failure (ALF) with hepatic encephalopathy, insidious onset lasting few months to few years until diagnosis, onset with complications of cirrhosis and portal hypertension or incidental finding without any symptoms(1).

Case report

We report the case of a 7-year-old girl, who was admitted in our department for the investigation of increased transaminases, discovered incidentally, the values exceeding three times the upper normal limit. The elevated transaminases were firstly observed three years before admission.

At the moment of admission, the patient had no symptoms. The physical examination revealed a well-nourished girl with a weight of 19 kg and a height of 119 cm. She had normal colored skin, normal cardiovascular and respiratory examination, respiratory rate 18/min, heart rate 70/min, without hepatosplenomegaly. The laboratory analyses revealed increased transaminases (aspartate aminotransferase, AST 99 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase, ALT 92 IU/L), without cholestasis. The coagulation (prothrombin time and INR) and serum albumin level were within normal limits. The serologies for hepatitis A, B, C, cytomegalovirus infection, Epstein-Barr virus infection, and herpes simplex virus were negative. Alpha-1 antitrypsin (A1AT) deficiency and Wilson’s disease (WD) were excluded due to the normal level of A1AT, ceruloplasmin, and 24-hour urinary copper excretion.

The serum level of the IgG was normal, but she presented IgA deficiency (11 mg/dl). ANA (1:80) and SMA (1:320), performed by immunofluorescence, were positive. Given the possible association of AIH with other autoimmunities (in 20% of the cases), we excluded autoimmune thyroiditis (normal TSH and fT4, negative thyroid peroxidase antibodies) and coeliac disease (negative antitransglutaminase IgA and IgG antibodies). The abdominal ultrasound revealed a normal homogeneous echotexture of the liver and a normal spleen size. MRCP was not performed. Also, we could not perform the liver biopsy due to the refusal of the parents. Transient elastography of the liver (Fibroscan) indicated the absence of fibrosis (F0 Metavir). Based on the laboratory findings, we established the diagnosis of AIH-1 and we initiated the treatment with prednisone at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day. The evolution was rapidly favorable, with decreasing transaminases after two weeks. After six weeks of treatment, the transaminases were within the normal range, and then we reduced the prednisone dose to the maintenance dosage of 5 mg/day. The transaminases remained within normal limits.

Discussion

AIH is a progressive inflammatory process of the liver, which can evolve unfavorably without proper treatment. AIH occurs within all ethnic groups, but the clinical manifestations vary with race and ethnicity. Alaskan natives have more frequently icteric AIH, Hispanics more commonly present with cirrhosis, and African Americans have accelerated disease progression. The estimated incidence for pediatric AIH varies from 0.23 to 0.4 per 100,000 person-years. In the past years, there has been an almost 50% increased in incidence in Western European countries(4).

The clinical manifestations of AIH in children vary from ALF, insidious onset with nonspecific manifestations (fatigue, abdominal pain, jaundice, headache), onset with complications of cirrhosis, or incidental finding of increased hepatic aminotransferases(1,5). This last category of the accidental discovery of elevated transaminases, including the case of our patient, constitutes less than 5% of the patients diagnosed with AIH in retrospective studies. Still, the actual prevalence cannot be accurately estimated(1,6). Most children with AIH have clinical signs of underlying chronic liver disease, including cutaneous stigmata (spider naevi, palmar erythema, leukonychia, striae), firm liver and splenomegaly. The course of the disease can be fluctuating, with flares and spontaneous remissions, a pattern that may result in delayed referral and diagnosis(6).

The most representative features of AIH are the female predominance (75%), hypergammaglobulinemia (IgG), circulating autoantibodies and interface hepatitis on biopsy(7,8). However, in 15-25% of the patients, IgG serum levels can be within normal limits, as in our patient. Also, IgA deficiency is present frequently in AIH-2, in almost half of the patients, unlike AIH-1, with only 7%(1,6,8). IgA deficiency has long been associated with several autoimmune diseases, especially coeliac disease, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus(9).

The clinical manifestations and the treatment are similar in both types, but there are some differences in prevalence and prognosis. AIH-1 is most frequent in adolescents and young adults, while AIH-2 presents at a younger age, including infancy. Regarding the disease prognosis, AIH-2 evolves more frequently with ALF, and the remission is challenging to be induced and maintain(1).

The autoantibody cut-off differs in children from adults. A lower titer is considered positive in children: >1:20 for ANA, >1:10 for SMA, and any titer are significant for anti-LKM-1(1,10,11). Anti-LKM-1 are positive in less than 5% of patients with chronic hepatitis C and AIH-1. Autoantibodies profiles for AIH-1 and AIH-2 can appear simultaneously in very rare cases(1,10). Our patient has features from both subtypes. The positive autoantibody profile (ANA, SMA), the mild evolution (possible evolving for three years without any clinical manifestations) and the rapid response to treatment support the AIH-1 type. In contrast, the young age of onset, IgA deficiency, and positive anti-LKM-1 are frequently present in AIH-2.

In both types of AIH, there is often a positive family history for other autoimmune diseases. Approximately 20% of AIH patients develop another autoimmunity such as thyroiditis, coeliac disease, IBD, hemolytic anemia, idiopathic thrombocytopenia, glomerulonephritis, hypoparathyroidism, insulin-dependent diabetes or vitiligo. It is essential to actively search for these conditions on follow-ups for prompt treatment(1,12). There was no family history of autoimmunity in our patient, and we did not find other autoimmune disorders associated.

The diagnosis of AIH is based on clinical, biochemical, immunological features and on histological changes. It is necessary to exclude other causes (viral hepatitis B, C, WD, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and drug-induced lived disease)(1).

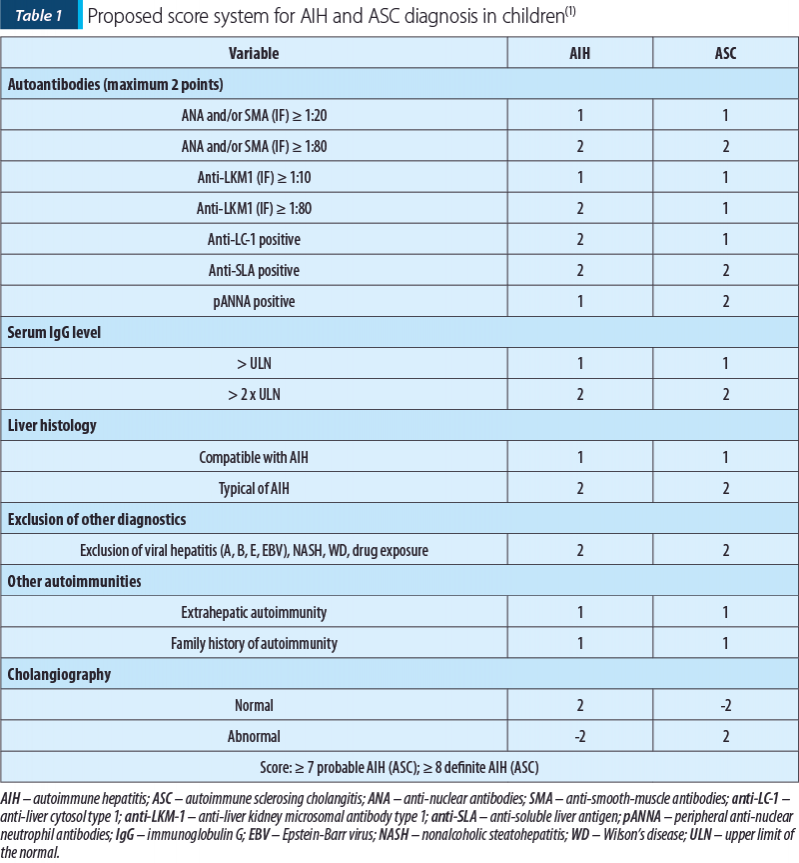

A scoring system was proposed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG)(7). This score includes clinical, immunological and biopsy criteria, excluding other causes of liver damage. It can also include HLA haplotype, the association of another autoimmunity, and response to treatment to classify AIH as possible or defined. However, this scoring system was designed for research purposes and is unsuitable for pediatric AIH(1,7). The IAIHG scoring system was revised in 2008, when a more simplified version was proposed for clinical use in AIH diagnosis. However, this score did not include either MRCP, therefore it is not suitable for diagnosing overlap syndromes since they cannot differentiate ASC from AIH(13-15). Given the need for a proper scoring system applicable for pediatric diagnosis of AIH and ASC, ESPGHAN proposed a scoring system that includes cholangiography alongside positive autoantibodies, IgG level, liver biopsy, exclusion of other causes of hepatitis, and association of other autoimmunities (Table 1)(1). MRCP was proven to have a high sensitivity (84%) and accuracy (84%), and it is recommended as the investigation of choice for the evaluation of biliary diseases in children(16). Recently, a score for pediatric AIH was proposed, including autoantibodies (0-2 points), hypergammaglobulinemia, exclusion of viral hepatitis and WD (1 point each), and liver histology (3 points), associated with a normal cholangiogram. A score ≥6 had a sensitivity of 95.8% and a specificity of 100% for AIH diagnosis, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 97.1%(17).

Although it has a high sensitivity (up to 95%), we could not apply this score for our patient, due to the lack of hepatic biopsy and cholangiography. A scoring system could be helpful for the diagnosis of AIH but, given the heterogeneity of these cases, not meeting the criteria does not exclude the diagnosis in a particular patient.

The treatment for AIH-1 and AIH-2 consists of immunosuppressive agents regardless of liver impairment. The first-line treatment consists of prednisone or prednisolone in a dose of 2 mg/kg (maximum of 60 mg/kg), which is gradually decreased in a period of 4 to 8 weeks, in concordance with the decrease of transaminase levels, to a maintenance dose of 2.5-5 mg/day. The response rate varies between 60% and 90%. Remission is defined as transaminase levels in the normal range, normalization of IgG levels, negative or very low autoantibody titer, or the histological resolution of the inflammation(1,18). Our case had a good evolution on prednisone alone. The second immunosuppressive drug used in AIH is azathioprine. Two ways of initiating azathioprine treatment are accepted: together with prednisone from the beginning or added in the presence of serious steroid side effects, or if the transaminase levels stop decreasing on prednisone alone. The azathioprine treatment is started with 0.5 mg/kg/day and can be increased to 2-2.5 mg/kg if signs of toxicity are not present. About 85% of patients require azathioprine association in the treatment(1). The immunosuppressive therapy duration is not clearly defined, but the recommendations are for at least three years of biochemical remission before beginning a gradual withdrawal to ensure histological resolution. Liver transplantation represents an option for unresponsive patients, end-stage chronic liver disease and ALF, but the posttransplant recurrence is frequent, despite immunosuppressive therapy, especially in ASC patients(1,19).

For our patient, we expect a favorable evolution due to the rapid response to treatment. We hope to be able to maintain the remission with a low dose of prednisone.

Conclusions

We reported a patient diagnosed with AIH-1 with no clinical manifestations, presenting only an increase of transaminases with normal IgG and IgA deficiency, with positive ANA, anti-SMA, and also anti-LKM-1 autoantibodies. This case emphasizes the importance of considering AIH diagnosis in any child with elevated transaminases, regardless of age and symptoms, given that the incidence of this disorder is rapidly increasing.

Bibliografie

-

Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Baumann U, Czubkowski P, Debray D, Dezsofi A, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Paediatric Autoimmune Liver Disease. Journal of Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2018;66(2):345-360.

-

Caveman’s Z, Beiraghdar F, Saburi A, Havisham A, Amirsalari S, Movahed M. Paediatric Autoimmune Hepatitis in a Patient Who Presented with Erythema Nodosum: A Case Report. Hepat Mon. 2012;12(1):42-45.

-

Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy K. Diagnosis and Management of Overlap Syndromes. Clinics in Liver Disease. 2015;19(1):81-97.

-

Mack CL, Adam D, Assis DN, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis in Adults and Children: 2019 Practice Guidance and Guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology.2020;72(2):671-722.

-

Grama A, Aldea CO, Burac L, et al. Etiology and Outcome of Acute Liver Failure in Children – The Experience of a Single Tertiary Care Hospital from Romania. Children. 2020;7(12):282.

-

Floreani A, Liberal R, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis: contrasts and comparisons in children and adults – A comprehensive review. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2013 Oct;46:7-16.

-

International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report. Review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1999;31:929–938.

-

Gregorio GV, Portmann B, Reid F, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in childhood: a 20-year experience. Hepatology. 1997;25(3):541-7.

-

Latiff AH, Ken MA. The clinical significance of immunoglobulin A deficiency. Ann Clin Biochem. 2007;44(Pt.2):131–139.

-

Cancado ELR, Abrantes-Lemos CP, Terrabuio DRB. The importance of autoantibody detection in autoimmune hepatitis. Front Immunol. 2015;6:222.

-

Vergani D, Alvarez F, Bianchi FB, et al. Liver autoimmune serology: a consensus statement from the committee for autoimmune serology of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. J Hepatol. 2004;41:677-83

-

Guo L, Zhou L, Zhang N, et al. Extrahepatic autoimmune diseases in patients with autoimmune liver disease: a phenomenon neglected by gastroenterologists. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:2376231.

-

Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Parés A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48(1):169–76.

-

Regan l, Ebbeson L, Schriber RA. Diagnosing Autoimmune Hepatitis in Children: Is the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Scoring System Useful? Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2004;2(10):935–940.

-

Boberg K, Chapman R, Hirschfield G, Lohse A, Manns M, Schrumpf E. Overlap syndromes: The International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) position statement on a controversial issue. Journal of Hepatology. 2011;54(2):374-385.

-

Chavhan GB, Roberts E, Moineddin R, Babyn PS, Manson DE. Primary sclerosing cholangitis in children: utility of magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(8):868-73.

-

Archos-Machancoses JV, Busoms CM, Tatis EJ, et al. Development and validation of a new simplified diagnostic scoring system for paediatric autoimmune hepatitis. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2019;51(9):1308–1313.

-

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63(4):971-1004.

-

Liberal R, Zen Y, Mieli-Vergani G, Veganic D. Liver transplantation and autoimmune liver diseases. Liver Transplantation. 2013;19(10):1065–1077.